A Proof of the Universal Approximation Theorem.

Hello there! It's been a long while...

You might have seen my LinkedIn post regarding my absence and what I've been doing while away, so I won't get into any details to catch you up on that front. But I will admit that I have been putting away posting this piece for a while now. The reason? Well let's just say that I've been planning (and I'm in the midst of) some other projects right now :)

I hope to write on that project sometime really soon, but I won't hype it up or anything for now (it is really cool though).

Anyways, back to the actual article at hand: The Universal Approximation Theorem.

WHAT IS THE UNIVERSAL APPROXIMATION THEOREM?

Well, the simple answer is that it is a mathematical theorem that shows us that a neural network of arbitrary width (or depth) is capable of approximating any function in the known universe. In layman's terms, it is mathematical proof that a neural network can learn anything in the known universe. Anything.

Now, for the high-level answer:

This is not a singular theorem in itself, it is much rather an amalgamation of several 'child' theorems (I don't want to use 'corollaries' because that sort of trivializes the results of each of these theorems). Amalgamated, they are different theorems - one proves that a neural network of arbitrary width is sufficient to approximate any known continuous function. Another does this for arbitrary depth. There's also been studies on bounded-depth and bounded-width networks that can approximate continuous functions.

The bottom line is that the theorems (any of them) argue that a network with non-polynomial activation functions can approximate a function to any degree of accuracy.

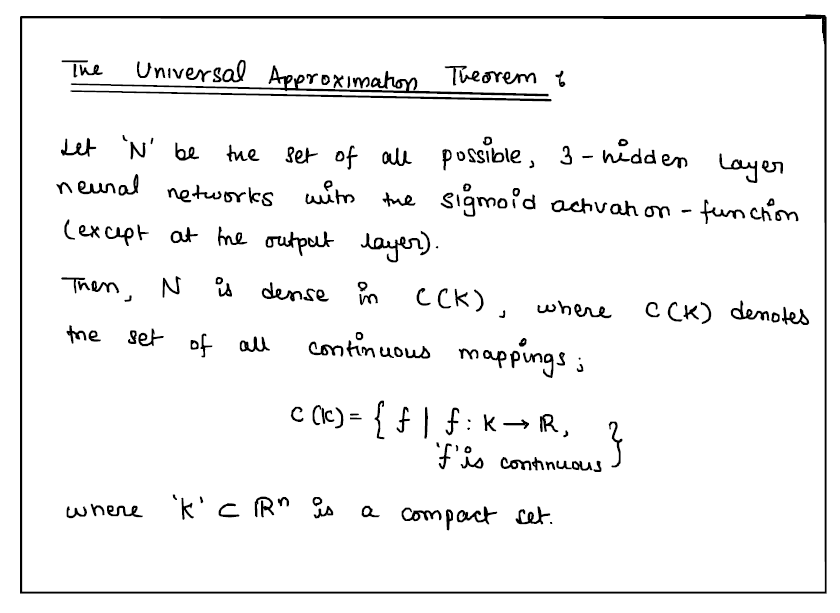

So, the formal statement of the theorem we'll work with is this -

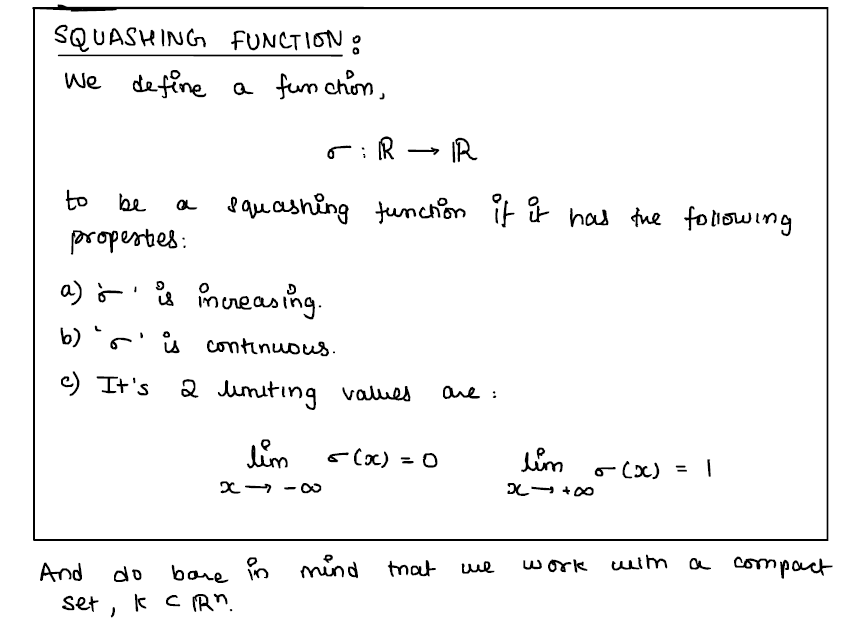

Let's introduce our tools first -

Do note that those limiting values needn't be 0 and 1 respectively. They can be any arbitrary real values $a$ and $b$, so long as $a < b$, where: $$\lim_{x \to -\infty} \sigma(x) = a \qquad \lim_{x \to +\infty} \sigma(x) = b $$

Now, pick any arbitrary function, $f \in C(K)$. Next, suppose we have the set $K$ to be a compact subset of $\Reals^{n}$ (as we supposed before). Also assume that all the hidden layers of our network, except the output layer, all have $\sigma$-activation functions.

We now begin to model the space of all possible such networks, layer-by-layer:

CONSTRUCTING THE NETWORK.

Network width is not an important constraint here, so don't worry about it.

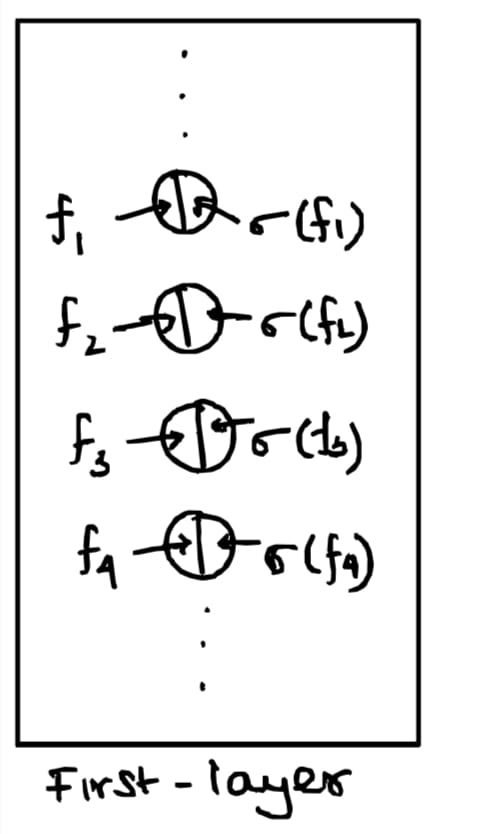

The First Layer -

Let $N_{1}$ be defined as the set of all possible functions of the form $f : \Reals^{n} \to \Reals$, where $x$ is our $n$-dimensional, real-valued input to the network. Formally: $$N_{1} = \lbrace f | f(x) = w_{0} + \sum_{i=1}^{n} w_{i}x_{i}; w \in \Reals^{n+1} \rbrace$$

Essentially, each neuron in the first layer is an element of $N_{1}$. This is how I think of it:

This is the same 'intuition' we'll run with for later layers as well.

Now, by composition of functions, as our squashing-function is continuous, we can model the set of all possible 'activated'/post-activation functions for each of the neurons as: $$N_{1}^{\sigma} = \lbrace \sigma \circ f | f \in N_{1} \rbrace$$

Clearly, each element of $N_{1}^{\sigma}$ is a continuous function. This is very important to note, as trivial as the fact may be.

Subsequent Layers -

Here is where we sort of apply composition of functions on a grander-scale, because that's what neural networks are - function compositions. As Neel Nanda put it (and I may be misremembering the exact thing he said) - "Turns out, linear spaces with non-linearity combined give us the most powerful objects in the universe!".

(If he didn't say that, I'm stealing it...)

Assume that our first layer was of width $k$. That is, we have some $k$-elements to choose from the set, $N_{1}^{\sigma}$ (more intuitively, our first layer had $k$-neurons). Now, since we are working with fully connected networks alone, we know that each of the $k$-outputs will be transmitted to each of the neurons in our $(m+1)$-th layer ($m \geq 1$) here. Bear in mind that I haven't defined the width of this $(m+1)$-th layer.

So for this layer, we define each of the possible functions in each neuron to be an element of the set $N_{m+1}$, where: $$N_{m+1} = \lbrace g \in C(K) | g = a_{0} + \sum_{j=1}^{k} a_{j}F_{j}; F_{j} \in N_{1}^{\sigma} \rbrace$$

(I need not have to say that $a \in \Reals^{k+1}$ for the above set.)

And finally, for any $(m+1)$-th layer like so, we wrap up the function in the sigmoid so that we can model the 'activated'/post-activation function that rests in each of the neurons in the layer itself. $$N_{m+1}^{\sigma} = \lbrace \sigma \circ g | g \in N_{m+1} \rbrace$$

Some results that can be easily seen are -

- $N_{m}^{\sigma} \subset N_{m+1}$

- $∀ f_1, f_2 ∈ N_m \text{ and } ∀ k_0, k_1, k_2 ∈ ℝ, \quad k_0 + k_1 f_1 + k_2 f_2 ∈ N_m$

A small bit of elementary math (like vector spaces), and you can easily reason why the above are true!

With that, we're done defining the network itself.

THE 3 LEMMAS.

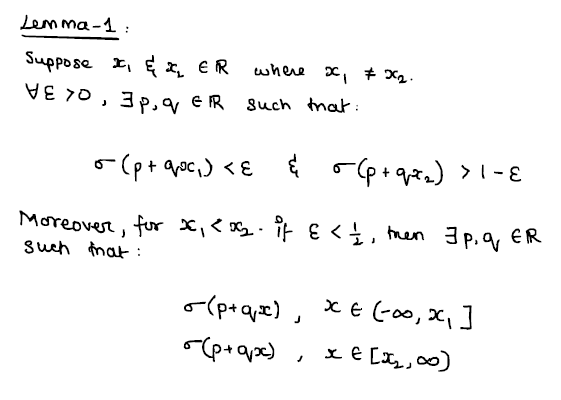

The first lemma is what I imagine as the '$\sigma$'-lemma. The idea behind this lemma is that, for a squashing function, it will basically act as a 'point-separator'. The lemma, when stated, goes as so:

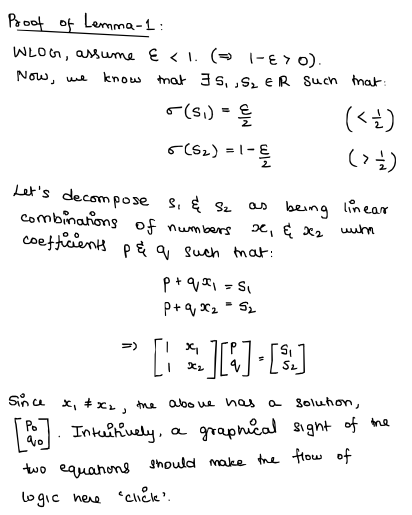

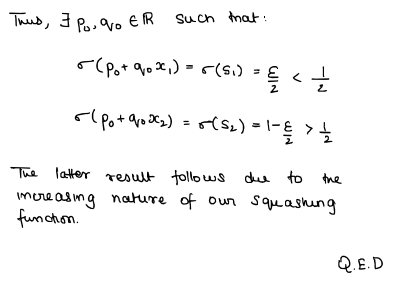

There's really no other way I can explain the idea behind this lemma other than just say that 'the sigmoid/squashing function we have is capable of separating points by sending each of them to distinct parts of its range.' That's literally all there is. The proof to it is as simple as well:

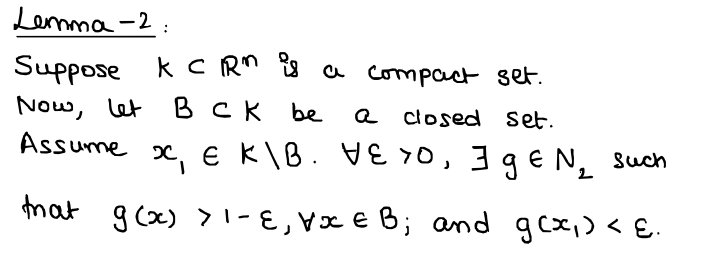

We now move to the second proof, which is, err, a bit less intuitive I guess. There's a bit of definitions and notions in there, which I won't get into right now because I can literally spend a couple of articles explaining what these ideas and concepts are. So, for now, these proofs remain as black boxes (even though they're really not I swear, I'm just super sleep deprived while writing this. I might update this part with the intuition once I'm caught up on sleep...)

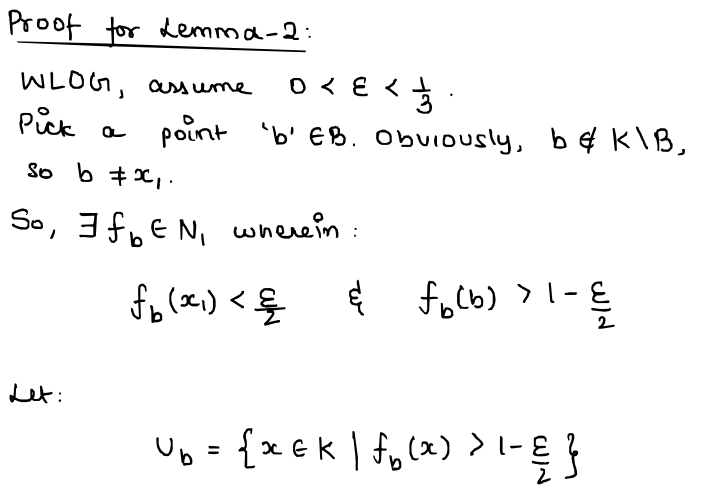

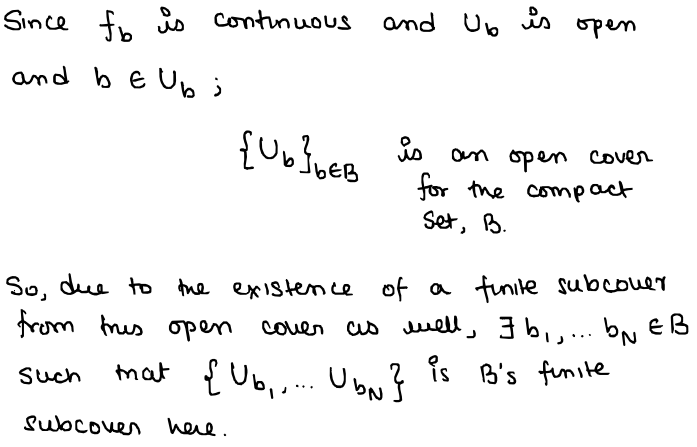

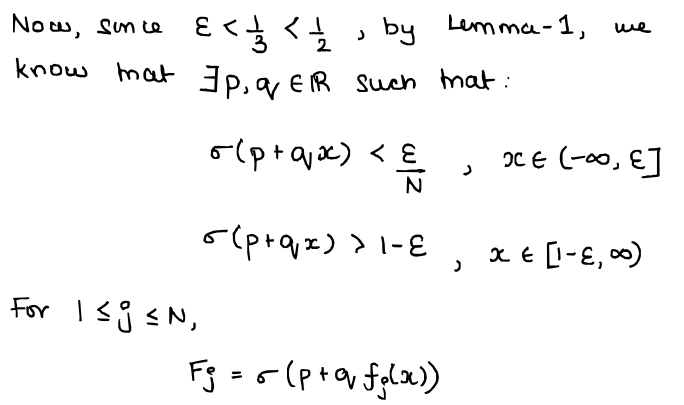

And its proof:

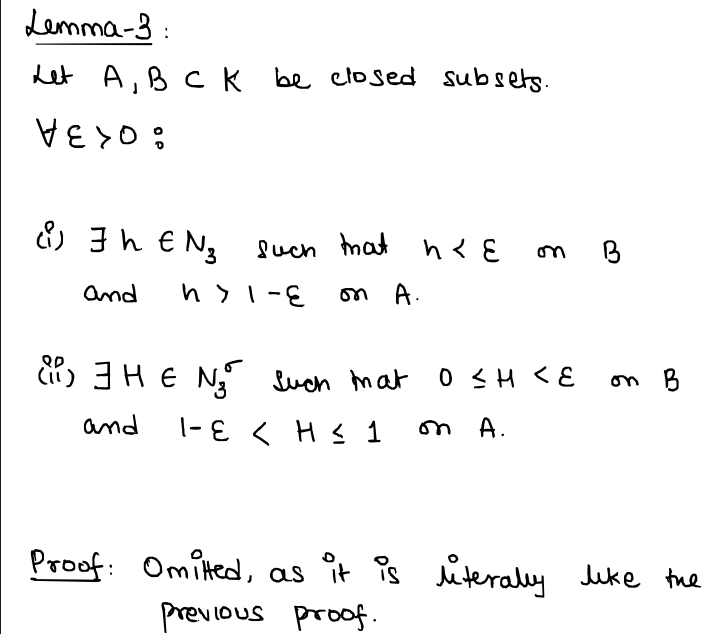

Now, I'm not-sleep-deprived enough to know that the proof to the 3rd lemma I'm about to present is extremely similar to this 2nd lemma's. It literally involves similar machinery and stuff, so I'm gonna be a bit lazy and just dump the lemma here, without proof, for you all to accept (you can read the proof in the original paper that I referred to for this write-up here):

THE PROOF.

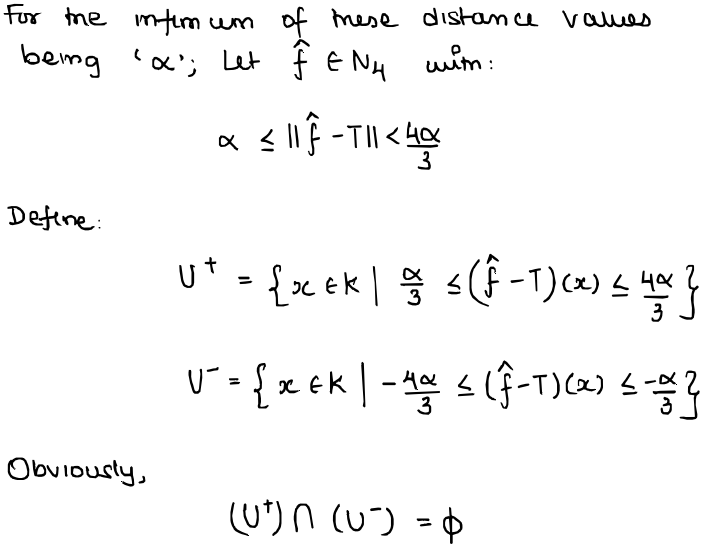

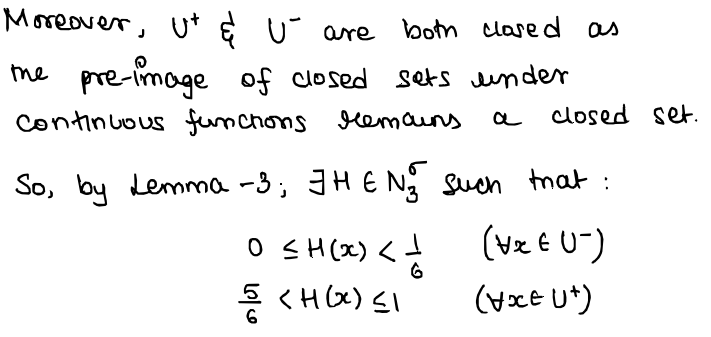

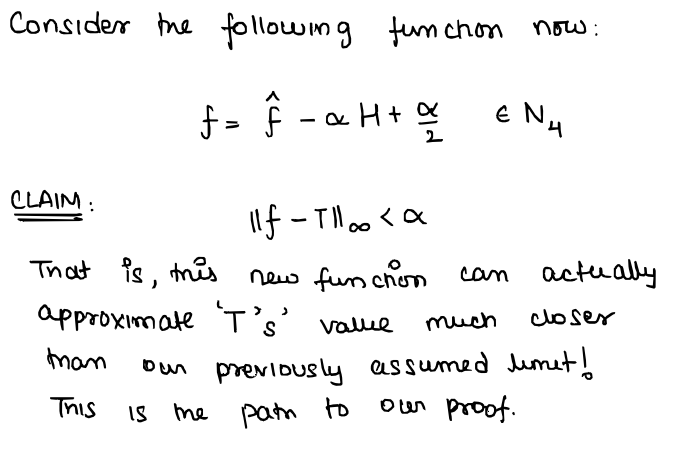

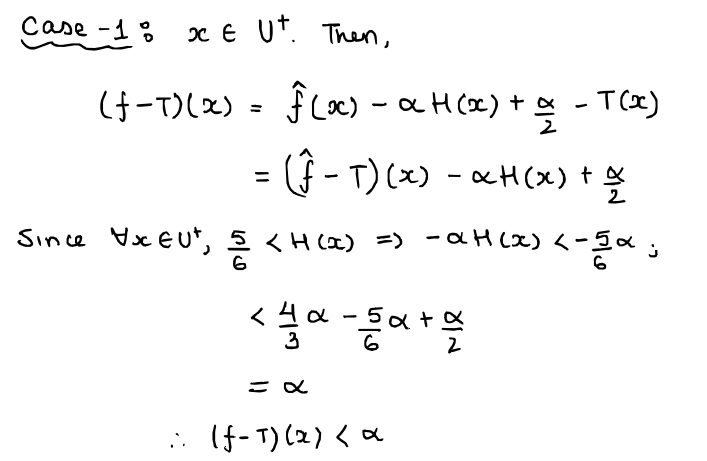

Now for the main event. The proof to our statement of the universal approximation theorem. A disclaimer: The author in the original paper referred to a function $f \in N_{4}$ to mean the output of a 3-hidden layer neural network itself, not a function in some 4th layer or something!

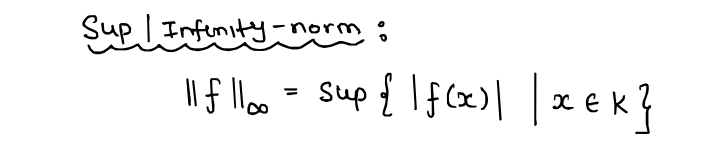

With that, we begin with a small reminder of what the $\| .\|_{\infty}$-norm is...

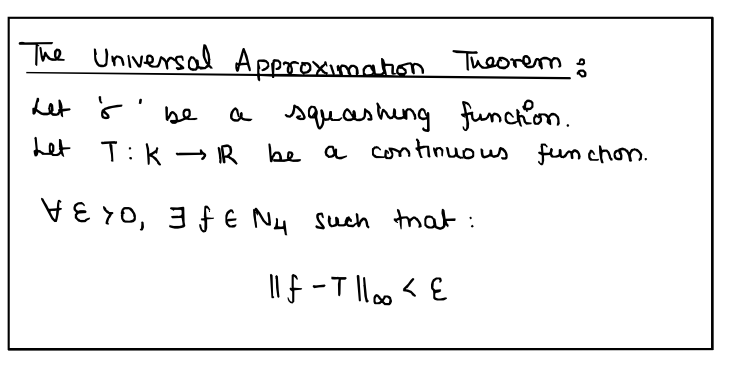

...a statement of the universal approximation theorem we'll prove (once again...):

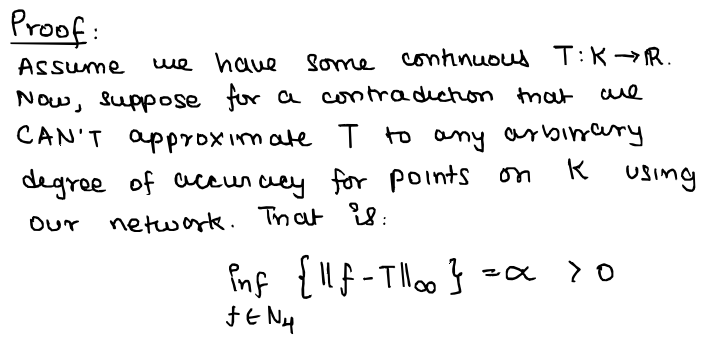

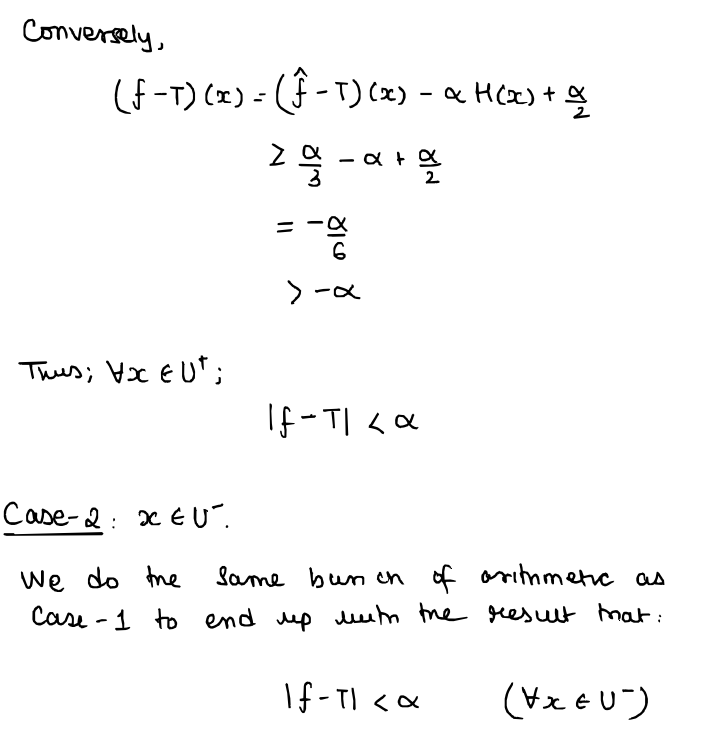

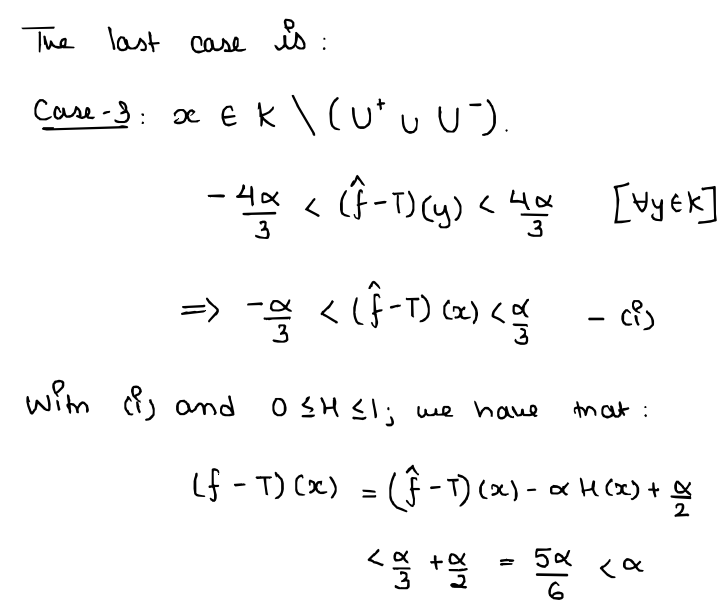

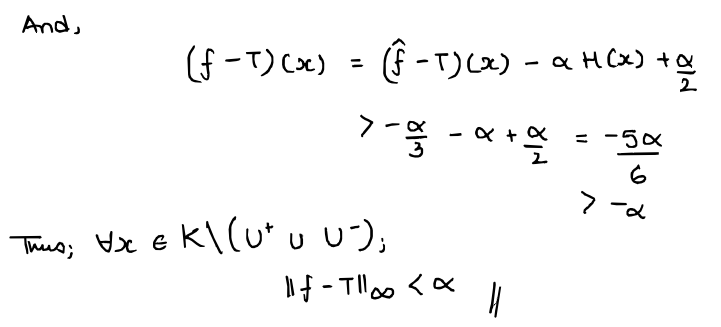

...and now with the main course of the day: the proof!

...but note that $f \in N_{4}$ and $\| f - T\|_{\infty} < \alpha$. Thus, we obtain our contradiction and we're done!

I hope you enjoyed this read! It was fun to write this as well (so much fun in fact, that as I was going to bed at 10:00PM right now to fix my sleep schedule, an idea on how I could break down the original paper clicked and I just couldn't leave it till morning! So, I present to you this article, after 6 hours of writing and breaking down the paper itself, on top of the hours of work I had put in much earlier when I was creating notes on the original paper).

Really exciting things coming up for future articles too, but again, I'm not going to hype up stuff so prematurely.

So until then, I bid you adieu 👋👋!!